Executive Summary

Taiwan’s relationship with China continues to improve and expand. Yet the eroding cross-Strait military balance must be redressed so that Taiwan can approach the political dialogue from a position of confidence and strength.

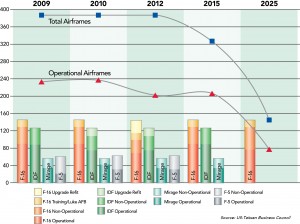

Effective air defense is a crucial component if Taiwan is to mount a viable defense of the island. Taiwan’s current air defenses comprise 18 fighter squadrons with a nominal strength of 387 combat aircraft of U.S., French, and indigenous origins: 145 F-16A/Bs, 126 F-CK-1A/Bs, 56 Mirage 2000-5s, and 60 F-5E/Fs. All of these are reasonably modern “Fourth Generation” fighters with BVR AAM capability, with the F-5s – which are mainly used for operational conversion training with only a secondary combat role – as the exception.

The Taiwan Air Force (TAF) also controls ground-based air defense forces in the form of over 25 medium/long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries, using a mix of U.S. and indigenous missile systems (I-HAWK, Patriot, and Tien Kung-I/II). TAF has three existing PAC-2+ batteries (currently being upgraded) and is in the process of procuring 6 additional operational Patriot systems, for a total of 9 active PAC-3 batteries. There are also a number of short-range air defense SAM and gun systems, as well as field air defense assets operated by Taiwan’s ground forces.

In addition, Taiwan has a sophisticated integrated air defense command & control (C2) system, together with a modern network of ground-based surveillance radars and E-2 AEW&C aircraft. The air defense C2 infrastructure is currently being hardened, further modernized, and integrated with new capabilities such as the Link 16 datalink and the Surveillance Radar Program (SRP).

Taiwan’s air defense forces confront a unique threat environment involving long-range SAMs and over 1,300 tactical ballistic missiles (TBMs) and land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs), which could – in concert with manned strike aircraft, UAV, information warfare/electronic warfare and Special Operations Forces (SOF) attacks – threaten their bases and C2 installations. To defend against an integrated Chinese air campaign, Taiwan is investing heavily in active missile defense, BMC3I, and early-warning capabilities. But the runways at TAF air bases are vulnerable, and damaged runways could disable defensive air operations.

Block obsolescence is also a clear and present challenge to the TAF. Its F-5 fleet is nearing the end of its useful structurally-permitted service life, and is slated to retire by 2014. In addition, the actual number of airworthy twin-seat F-5Fs was reduced to just four aircraft in 2009. This shortfall is impacting lead-in fighter training (LIFT) for new pilots, and could erode pilot quality and operational readiness over time. Similarly, Taiwan will also need to address block obsolescence and reliability issues of its I-HAWK SAM systems.

Taiwan does not currently have a cost-effective means to address TAF’s fighter capability shortfall caused by F-5 obsolescence. Taiwan’s Mirage 2000 fleet suffers from very high Operations & Maintenance (O&M) costs and chronically low availability rates. The TAF poured substantial funding into addressing the Mirage issues over the past two years, leading to recent improvements in material readiness. But a tight O&M budget situation will almost certainly ensure a relapse into low Mirage material readiness over the next few years. Taiwan may resort to mothballing part of the fleet to conserve resources, and the combination of F-5 obsolescence and strained Mirage supportability will create a substantial shortfall of fighter aircraft for the TAF.

Meanwhile, China continues to aggressively introduce large numbers of modern combat aircraft into service. China currently deploys more than 700 combat aircraft within operational range of Taiwan, with hundreds more in ready reserve. These include over 500 very modern aircraft (Su-27, Su-30, J-10, JH-7), which are roughly comparable to TAF’s “Fourth Generation” aircraft types (F-16A/Bs, Mirage 2000-5s, F-CK-1A/Bs).

Conversely, TAF fighter strength is projected to decline to only around 300 aircraft by 2014-2015, and thus China will easily be able to array a better than 2:1 numerical superiority. Taiwan will then no longer have the number of combat aircraft necessary to meet the requirements for defending its air space from Chinese military threat.

The significant quantitative decline in air defense capability that Taiwan is expected to experience over the next several years could also have a profound and enduring impact by eroding the already marginal qualitative edge still held by Taiwan. Lessons from past Taiwan Strait crises have demonstrated the importance of Taiwan maintaining a qualitative edge against China, not only to prevail in conflict but also to strengthen deterrence.

The inability to provide timely replacements of obsolete equipment and/or prevent further deterioration in material readiness could result in Taiwan permanently losing its traditional edge in training and experience. Thus the current situation is both widening the quantitative gap in the cross-Strait power balance, and narrowing TAF’s qualitative edge in aircraft performance and pilot training/experience.

The principal mission requirements for the TAF are Combat Air Patrol (CAP), Defensive Counter-Air (DCA), Maritime Strike/Anti-Invasion, and Missile Defense (TBM/LACM). To carry out these missions, TAF will need a modern fighter aircraft with sufficient aerodynamic performance, BVR missile capability, and payload/range performance to effectively counter the expected Chinese aerial threats. Taiwan will also need upgraded SAM systems to engage TBMs and LACMs.

A review of the operational scenarios indicates that Taiwan’s current air defense forces are only marginally capable of meeting the island’s air defense needs. With effective fighter strength weakened by a combination of obsolescence of the F-5E/F fleet, low material availability of the Mirage 2000-5 aircraft, and obsolescence/declining reliability of I-HAWK SAM systems, Taiwan’s ability to defend its air space against likely threat scenarios can be expected to significantly deteriorate over the next few years.

TAF urgently needs to procure new combat aircraft to compensate for the significant loss in operational fighter strength projected over the next 5 years. The fighter gap, if not bridged in a timely manner, could solidify cross-Strait military imbalance in favor of China. That would both undermine deterrence and expose Taiwan to Chinese political extortion as the two sides move towards political dialogue.

A suitable candidate aircraft has to possess sufficiently high performance, BVR capability, and payload/range characteristics to conduct the CAP/DCA and maritime-strike/anti-invasion missions. Such aircraft also need to be supportable beyond 2025 and be export-releasable to Taiwan.

Given these criteria, the aircraft best suited to Taiwan’s current needs is the F-16C/D. Taiwan has been seeking U.S. approval for the sale of 66 new F-16C/D Block 50/52 fighters since 2006, but has been repeatedly discouraged by the U.S. Government to formally submit the associated Letter of Request (LOR). With the last F-16s under contract slated to be delivered at the end of 2013 – and given the 36-month manufacturing lead time – the production could be forced to close before a decision is made. Thus the window for Taiwan to purchase new-built F-16s is closing rapidly.

Another measure that could help address Taiwan’s predicament could include adopting a more rigorous, disciplined, life-cycle cost-based approach to force modernization planning and force management. Taiwan needs to implement a robust mid-life retrofit/modernization (MLU) program for its existing fleet of F-16A/B and F-CK-1A/B fighters, to address DMS/obsolescence issues, improve reliability/maintainability, improve survivability, and update aircraft capabilities.

Taiwan should exercise farsighted MLU investment choices in such systems as radar, electronic warfare systems, power plants, mission avionics, and air-launched weapons. Examples of such capabilities could include an active electronically-scanned array (AESA) radar and an upgraded engine, which could provide force-multiplying capabilities by significantly enhancing engagement capability per platform.

Taiwan should also consider further improving its ground-based air defense capability, through a combination of acquiring additional PAC-3 and other mobile SAM systems, upgrading existing I-HAWK batteries, and introducing mobile, low-altitude air defense systems. Other major force-multipliers for Taiwan would be a modern, integrated intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capability, and additional investment in electronic warfare and information warfare (EW/IW) capabilities.

In addition to (and in combination with) maintaining a critical mass of air defense fighter capability and ground-based air defenses, Taiwan can also consider more asymmetrical approaches to the problem of integrated air defense, including passive defense measures (e.g. redundancy, dispersal, camouflage/deception, hardening, and rapid repair capabilities) and counter-strike capability (LACM, ARM, standoff-attack weapons).

In summary, Taiwan is facing a pressing fighter requirement that can best be met through acquisition of F-16C/D Block 50/52 aircraft from the United States. Taiwan can further strengthen its air defenses by investing intelligently in MLU programs for its F-16A/B and F-CK-1A/B fighters; by deploying more mobile SAM systems, upgrading existing I-HAWK batteries, and pushing ahead with its new low-altitude air defense system program; by developing advanced, integrated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities; and by adopting a number of asymmetrical measures.

A modernized and capable Taiwan air force could play an important and constructive role supporting U.S. forces in the event of a confrontation with China over Taiwan. In contrast, an absence of credible Taiwan airpower could accentuate U.S. vulnerabilities and negatively influence U.S. power-projection in the Pacific.

In addition, a stronger and more secure Taiwan can be expected to be more confident in its political dialogue with China, which could ultimately lead to a peaceful resolution of the situation in the Taiwan Strait. Such an outcome would certainly serve the national interest of the United States.

The U.S. can and should assist Taiwan in implementing these measures, to help strengthen deterrence and to support peace and stability in the region. Improving Taiwan’s defense capability will also help reinforce the positive steps that Taipei has taken in lowering cross-Strait tensions and expanding ties with Beijing.

This major report examining the cross-Strait balance of air power and Taiwan’s major air defense requirements is available on the US-Taiwan Business Council website:

“The Balance of Air Power in the Taiwan Strait” (PDF)

Key Report Graphic: Available Airframes Through 2025